The tourism workforce is an inherently diverse group. In 2021, the gender split matched that across the entire Canadian working population, but tourism employed a greater share of youth, immigrants, non-permanent residents, members of visible minorities, and speakers of multiple languages[1].

From a statistical perspective, this level of detail is most easily captured in the national census, which presents a very accurate snapshot of a moment in time. Unfortunately, the census is only conducted every five years, meaning it’s not a great tool to track ongoing and evolving shifts in the tourism workforce. For the most up-to-date indicators, we tend to look to the Labour Force Survey (LFS), a monthly estimate of employment that provides timely insights on trends and tendencies for the Canadian tourism sector, and for the economy overall.

Immigration as a Variable in the LFS

The LFS surveys around 68,000 households on a six-month rotation, which covers around 100,000 people. The results of the survey are scaled statistically to represent an approximation of the total Canadian population’s labour characteristics, and this national economy-wide estimate can be broken down into industry groups to provide sector-level information. Because the sample size is so much smaller than that of the census, the data is less reliable as an indicator a specific moment in time, but the design means that we can use it for longitudinal monitoring of what is happening at an aggregate level.

Tourism HR Canada purchases a custom dataset from Statistics Canada that is built around the Tourism Satellite Account. This ‘tourism slice’ includes an estimate of the immigration status of the workforce. In particular, it estimates how many people in the labour force (or in employment) were born in Canada and how many are landed immigrants. If you add these two categories together, the sum is less than the overall total—so there is a residual category that includes everyone who was neither born in Canada nor a landed immigrant. This ‘other’ group includes everyone working in Canada on a temporary work permit, as well as naturalized Canadian citizens and a few other configurations of citizenship/birthplace/work permits.

This ‘other’ category is the closest we can get, from an LMI perspective, to estimating temporary workers in Canada on an ongoing basis.

We previously published a comparison of this ‘other’ category estimate of temporary international workers with what was found in the census. The article concluded that it was an imperfect proxy for temporary workers, but not a bad one given the limitations on accessing timely data about temporary workers in Canada.

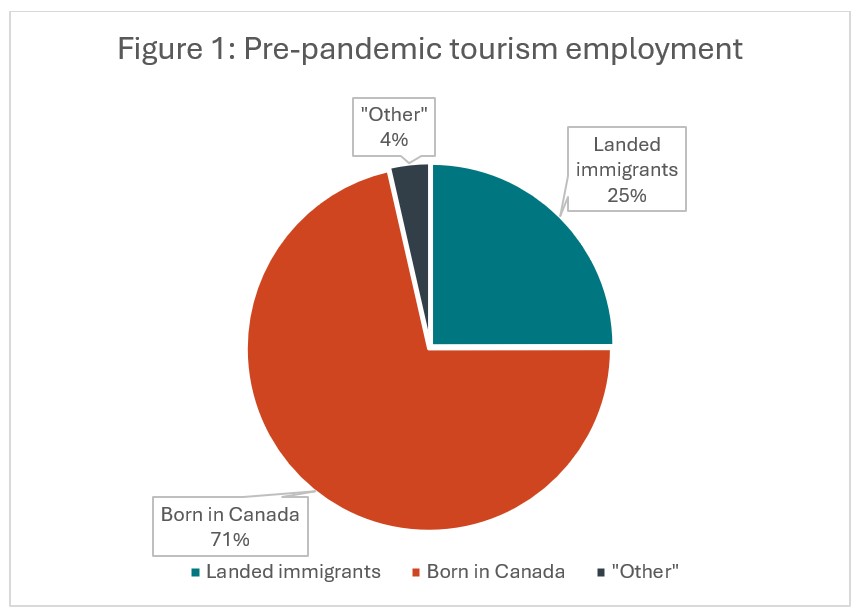

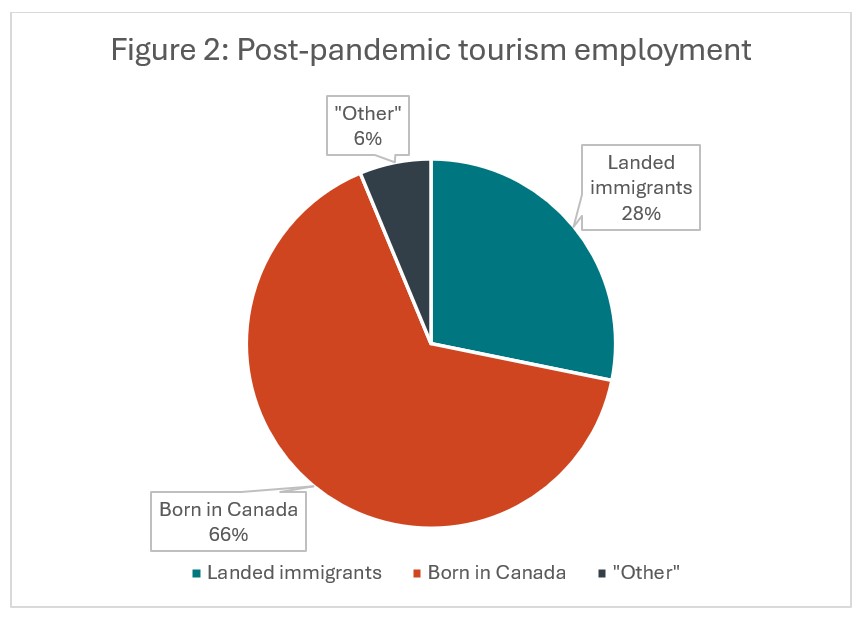

Figure 1 provides an estimate of the tourism workforce composition from January 2015 to February 2020, and Figure 2 provides one from May 2021 to October 2024. (The period of maximum pandemic disruption has been excluded, because the data pertaining to the tourism workforce were extraordinarily distorted from the sector’s usual distribution.) By summer 2021, things had begun to even out again, albeit at much smaller numbers—but the shares of the workforce began to stabilize, and shift towards the so-called ‘new normal’.

As we can see, the share of the tourism workforce that was born in Canada fell slightly (-5 percentage points), with the losses made up by landed immigrants (+3 percentage points) and those in the ‘other’ category (+2 percentage points). This means that tourism is providing more opportunities than ever to internationally trained workers, but also that the sector is becoming more vulnerable to shocks to the immigration system—which is exactly what we are anticipating with the latest changes in immigration policy.

Who Are These ‘Other’ Workers?

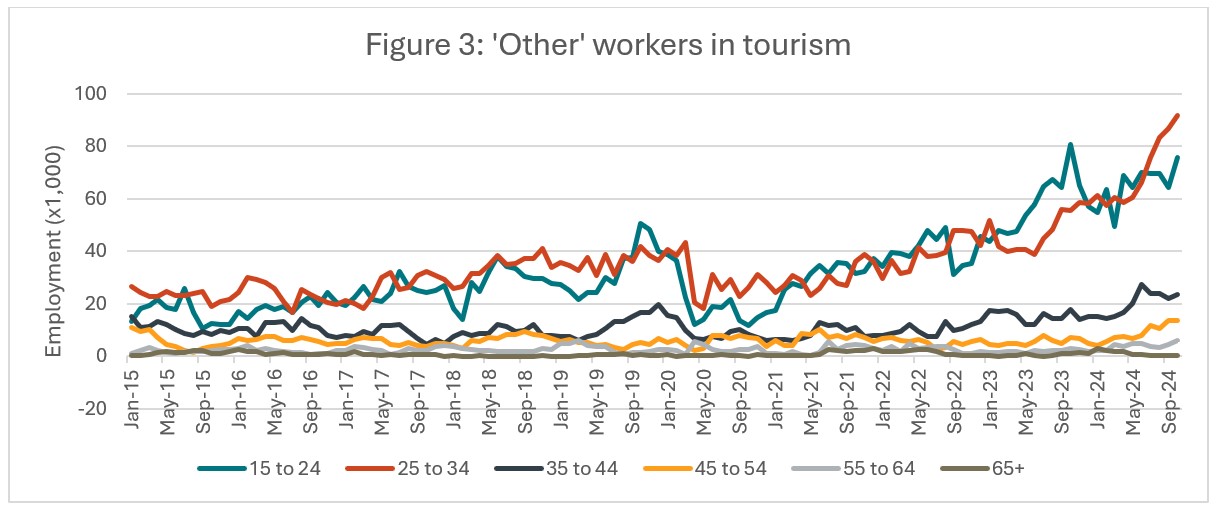

The data that we have doesn’t allow us to make any concrete groupings of who falls into this ‘other’ residual category of workers, but we are able to look at their ages (Figure 3).

Across the ten-year window that straddles the pandemic, we see that the two youngest age groups (15 to 24, and 25 to 34) have consistently made up the largest share of tourism workers, and their numbers were gradually increasing in the years up to the pandemic. There was a substantial drop-off in 2020, and since then, their numbers have been increasing even more rapidly than before.

The age distribution that has seen the sharpest acceleration gives us some clues as to who these workers are. A substantial proportion of them are likely to be international students on visas that allow them to work off-campus for a limited number of hours per week during term time, and unlimited hours outside of term time (over summer vacations, for example). We know that Canadian colleges and universities have seen rising numbers of international enrolments over the past several years, tied partly to funding constraints from their respective provinces, and also to the fact that studying in Canada can be one route into permanent immigration. We also know that tourism businesses are major employers of international students, regardless of what subject they’re studying. With caps being introduced on international student permits, the tourism sector stands to lose a substantial number of workers.

Another group that is likely well represented in these two age categories is those on an International Experience Canada (IEC) permit, more commonly known as a working holiday visa. These are short-term visas (usually one or two year) attached to open work permits, allowing the permit holder to work for any employer in Canada. Again, tourism businesses are a major employer of these young people, many of whom are working to pay their travel and living expenses while they explore Canada, meaning that tourism destinations are big attractors for them.

With both international students and IEC permit holders having open work permits, it isn’t possible to track which industries or employers they are working in, so we can’t provide a concrete estimate of how many of our young international workers fall into either of these categories. However, it is likely to be substantial.

There are numerous other temporary working arrangements that allow short-term employment in Canada, and likely account for the bulk of the older age groups as well as some of the younger ones in Figure 3. Because a number of these options also provide open work permits, it is just as impossible to know where they’re working as it is for students and IEC permit holders, but it is likely that they represent a sizeable share of the workers in question.

Temporary Foreign Workers

When most people think of temporary international workers, their minds go immediately to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP). This is certainly one of the most visible and politicized categories for international workers, and it has attracted a lot of media attention lately amid allegations of gross negligence and outright abuse. It’s also been attached to narratives of “cheap foreign labour” that is “displacing Canadian workers” and “driving up unemployment”. While this may have a ring of truth for some industries and sectors, the picture is more complicated in tourism.

The TFWP is a program that assigns permits attached to one employer and to one job, which makes them qualitatively different from open work permit programs. There are publicly available data sets that provide occupation-level information about how many permits were issued. These occupations are not categorised by industry, which means that we may be over-counting tourism permits. While it’s true that most Hotel front desk clerks (NOC 64314) probably work in a hotel and therefore in a tourism industry, the odds change for some other occupations. Many kitchen-related occupations, for example, may work in restaurants or hotels (which are tourism industries), but they may also work in hospitals, in prisons, in mining camps, in school, in long-term care facilities—none of which are classed as tourism.

But we can nevertheless take a look at occupations that represent a sizeable share of the tourism workforce, even knowing that we may be overestimating in some cases. We may equally be under-estimating, after all—we would not pull TFWP data on plumbers or electricians, for example, because even though they may be employed by a tourism business, the share of plumbers or electricians who are working in tourism would be far too small compared to those working in construction. So we undercount in some areas, and overcount in others, and hope that the final reckoning is not too out of balance.

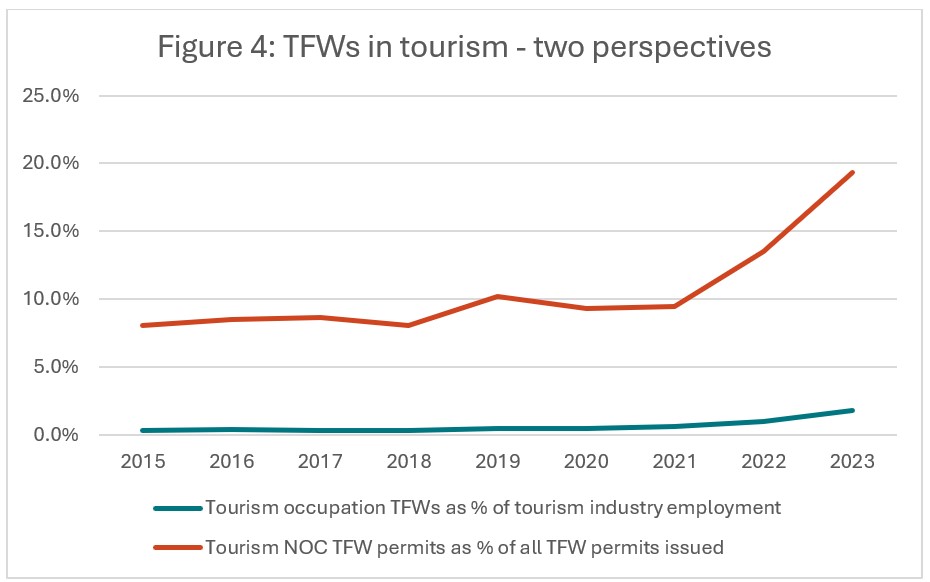

There are a few ways that we can look at the numbers from TFWP data and apply them proportionately to the tourism sector (see Figure 4). The first is to consider how many TFW permits have been issued to occupations closely associated with tourism, as a percentage of all TFW permits issued (the orange line). The data shows that, until the pandemic, tourism occupations made up around 8 to 10% of all TFW permits issued—given that the tourism sector employs around 10% of all working Canadians, this number is not wildly disproportionate. Since the pandemic, of course, the number of TFW permits issued for these tourism occupations has increased dramatically. We will come back to this observation in the next section.

The second way to consider tourism-occupation TFW permits issued is to compare them against the size of the tourism workforce (the blue line in Figure 4). This ratio compares the number of TFW permits issued for tourism occupations with the employment estimates from the LFS. While this is not a perfect match on many levels, it’s nevertheless a useful perspective. Prior to the pandemic, tourism occupation TFWs made up less than one percent of the total tourism workforce: 0.3% from 2015 to 2018, rising to 0.5% in 2019. By 2023, although the share had increased, it had only reached 1.8%.

So we come back to a recurrent theme from the webinar: there are two competing numbers on the same data point, and both of them are right. In this case, the difference is between tourism’s (probable) share of all TFW permits being issued, and the impact that those TFWs have on the tourism sector.

In all likelihood, this 1.8% of the tourism workforce is not distributed evenly. The complexity and cost associated with hiring a worker through the TFWP means that only a small percentage of tourism businesses actually make use of the program. This includes particularly large businesses such as hotel or restaurant chains, who have the resources to invest in this program, and who have dedicated HR personnel who can take on the administrative burden.

Busting the Myth of the Displaced Canadian Worker

The media narrative of the unemployed Canadian who is sidelined by an endless stream of cheap foreign labour is one that we are all familiar with: why should foreign workers come to Canada when there are Canadians looking for work? For tourism, at least, there are two counternarratives we need to consider: worker mobility, and skills.

Worker mobility refers to the ability of workers to go to where there are jobs. In an ideal world, the population would redistribute itself to where labour was needed—but we live in a world where that is often not possible. Someone who is established in Toronto, who has roots in their community and whose children and partner are also deeply embedded in the community, cannot simply uproot everyone and move to Saskatchewan for a job that likely pays less than what they would earn in Toronto. The financial and social pressures facing Canadians, and the infrastructure deficits across the country, are making it harder and harder for people to simply pack up and move for work. Even our most mobile workers, young people with a sense of adventure and a willingness to travel, find it nearly impossible to secure affordable housing in tourism destinations. Many employers find that they have to offer some form of staff housing just to maintain enough staff to stay in operation, but they cannot house all their workers, and as workers mature, they become less and less willing to live in the type of shared accommodation commonly available. Internationally trained workers, who have no particular ties to a specific part of Canada, have much greater mobility in many respects, and a willingness to live and work in places that Canadians are incentivized to leave.

The second rebuttal is around skills shortages. While it can be tricky to enumerate the specific skills needed to perform any particular job, to say nothing of how to assess the transferability of skills between jobs, there are nevertheless widely recognized differences between the skill levels required for different types of job. In Canada, we have an unfortunate tendency to equate formal education with skills, where jobs that require a university qualification tend to be seen as more highly skilled. While this may be true for many professional jobs—doctors, lawyers, engineers, for example—this systematically undervalues the skills inherent in trades, or in other unregulated fields of work. But in most workplaces, skills take on many different forms and types, and there are many paths to acquiring those skills.

Canada uses a classification system called TEER—Training, Education, Experience and Responsibilities—to categorize jobs hierarchically. The TEER system recognizes six groupings, summarized in Table 1[2]:

| Table 1: TEER classification system | |

| TEER | Occupation types |

| 0 | Management occupations |

| 1 | Occupations that usually require a university degree |

| 2 | Occupations that usually require a college diploma,apprenticeship training of 2 or more years, orsupervisory occupations |

| 3 | Occupations that usually require a college diploma,apprenticeship training of less than 2 years, ormore than 6 months of on-the-job training |

| 4 | Occupations that usually require a high school diploma, orseveral weeks of on-the-job training |

| 5 | Occupations that usually need short-term work demonstration and no formal education |

While the TEER system is a bit of a blunt instrument in many ways, it nevertheless provides a framework for classifying jobs by skill level, while recognizing that responsibility (accrued over time through experience) can be as important as formal education. Figure 5 provides a snapshot of the distribution of tourism-occupation TFW permits issued, grouped by TEER category.

Contrary to the widespread myth, the majority of tourism occupations for which TFW permits have been issued are for occupations at TEER level 3 or higher: that is to say, they are skilled jobs. The two most commonly granted TFW permits in 2023 were for Cooks (TEER 3) and for Food service supervisors (TEER 2), both of which rely on specialized skills acquired through a combination of formal training and work experience. These jobs cannot be filled by someone randomly drawn from a pool of unemployed Canadians.

TEER 4 and TEER 5 occupations were certainly among the permits issued, accounting for around 36% of permits from 2023, particularly for Food counter attendants, kitchen helpers and related support occupations (TEER 5) and Light duty cleaners (TEER 5). While these are both entry-level positions that could in principle be filled by anyone willing to be trained, the fact that businesses are willing to take on the expense and paperwork of going through the TFWP process speaks volumes on how difficult it is to find Canadians who are willing to take on those jobs. The lack of Canadians interested in these jobs may be an issue of mobility, but may equally be one of job desirability: if Canadians don’t want to work as Light duty cleaners, there is not much that can be done to change their minds, and hotels cannot operate safely without housekeeping room attendants. In the absence of a local option, it is no surprise that operators turn to programs such as TFWP to meet their operational needs.

Changes and Impacts

The current federal immigration strategy calls for dramatic reduction in both temporary international workers and permanent residents, phased in over several years. What will this actually look like?

In projecting potential workforce losses due to policy change, we have to assume that the most immediate impact will be felt in those businesses and industries that make use of short-term international workers, via whichever program they find more useful. These workers will disappear first because of the high turnover rates associated with this type of employment: as the current workers reach the end of their contracts and leave, many will not be replaced. There will also be a short-term impact in terms of permanent residents, but because they tend to have a lower turnover rate than temporary workers, the effect will build up more gradually and the full magnitude will not be felt for several years. Exactly how the reduction in permanent residents will affect the tourism sector in the short term is hard to quantify, because we do not have detailed enough data to make reasonable estimates of turnover rates for this group.

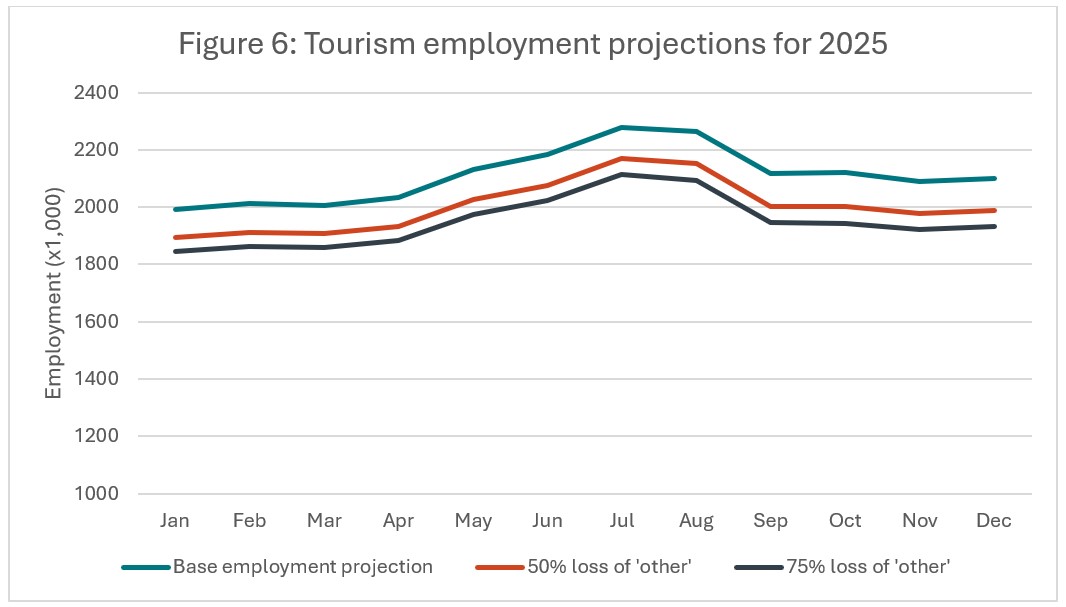

The projections in Figure 6 present three scenarios. The baseline (blue line) is projected on the assumption that nothing changes: it uses an estimate of year-over-year growth to project the overall annual average employment number, and then uses the seasonal distribution about that average to redistribute workers according to normal seasonal variation. Under this scenario, there are no reductions of immigrations or temporary workers in tourism.

The second scenario (orange line) assumes a 50% reduction in workers in the ‘other’ category. The federal immigration levels plan calls for a reduction of around 446,000 workers in 2025, and a further 446,000 in 2026. The ‘other’ category in the baseline projections accounts for an average of around 161,000 workers. Although the TFW permit holders in tourism represent a relatively small proportion of the workforce, we have strong evidence that students and other young international workers make up a substantial proportion of the labour pool for tourism. A reduction of around 50% in this ‘other’ category is a reasonable estimate for the impacts that we will be likely to see, as it accounts for around 18% of the total reduction in temporary workers, in line with the ratio of TFW permits issued to tourism occupations noted above for 2023. Under this 50% reduction scenario, the tourism sector stands to lose around 100,000 workers over 2025, which amounts to around 5% of the 2024 tourism workforce.

The third scenario (grey line) assumes a 75% reduction in the ‘other’ category. While this ratio is higher than would be indicated by anticipated changes to the number of temporary workers, this additional 25% is intended to reflect the early impacts of the changes to permanent residencies granted. Under this scenario, the sector stands to lose around 150,000 workers, or around 7% of the 2024 tourism workforce.

As with all projections, of course, this is guesswork based on certain assumptions that some elements of the system will stay unchanged, and others will change in particular ways. In the case of immigration and temporary resident targets and policies, it is likely that we will see more changes over the coming months and years. The current levels plan maps out reductions to 2027, and then sees a relative easing up of restrictions. With the volatile political landscape in which we operate, it seems unwarranted to project beyond 2025 at this point, as the degree of uncertainty is amplified the further into the future we try to forecast.

In the meantime, our sector will have to start to prepare for reduced employment numbers throughout the coming year, and take steps now to mitigate the seemingly inevitable challenges facing the coming summer season.

So What Next?

With the high likelihood of a protracted labour shortage throughout 2025 and probably well into 2026, the tourism sector is facing another challenging period. Coming so hot on the heels of the pandemic and its long and rocky recovery, the future may be looking a bit bleak.

But collectively, we have already begun to address these challenges. We recognize that businesses need to learn to work with smaller and more nimble teams, and there have already been improvements in that direction over the past few years: during the lean pandemic times, we all learned a lot about what we can and can’t do well with fewer people. One of the solutions has to be investment in skills development for our workforce, to improve productivity at a business level, but also to improve the customer experience at a service level.

The economic concept of productivity can be hard to pin down at an operational level in a sector like tourism, which is characterised more by consumption than by production, but it’s a useful frame to adopt in thinking about changes. How do we do more with less? Technology and AI may provide some inroads, particularly around targeted marketing material or business data analytics, but in a service-oriented sector like tourism, human to human contact remains central to the allure of tourism for many visitors. So the technology question becomes: how can we reduce the administrative and automatable elements of tourism jobs, and free up our people to deliver exceptional service?

We also need to shift our gaze in terms of attraction. We know that the tourism sector relies heavily on young workers, and it benefits enormously from international talent, but these two groups alone won’t close the gap that we’re facing. We need to create workplaces that are welcoming and supportive of people with disabilities, of seniors and mature workers, of Indigenous individuals, and we need to get serious in terms of collaborating to share workers between businesses. With static or shrinking pools of labour, and with increasing demand from tourists and increasing labour competition from other sectors and industries, we need to get smarter about who we attract, how we get their attention, and how we create workplace cultures they want to stay in.

The reality is that immigration will continue to be a pressure point for the sector for the foreseeable future. The policy landscape in Canada is dynamic, and in the event of a change in government, we may see radical shifts in policy and process. But this situation is not unique to Canada: around the world, we see patterns of increased border patrol, suspicion of immigrants, and stricter limits on temporary international workers. If this is part of the new normal, we will have to learn to operate in this emergent environment.

Tourism HR Canada continues to look for better and more timely data on immigration and temporary workers in Canada. The Labour Force Survey is an important cornerstone of our LMI system, but where it falls short on a few key indices, we need to find alternative sources of reliable and accurate data to inform how our sector responds to changes across the workforce. We will also continue to monitor policy changes and keep our stakeholders as informed as possible about the shifting realities around bringing international talent into the tourism sector.

This is the first in a series of articles looking at key topics that come out of our recent Losing Ground: The Definitive Workforce Update webinar. Be sure to subscribe to Tourism HR Insider for the next analysis.

Attended the Losing Ground webinar? We’d love to hear your feedback. Please fill in this short survey.

[1] The TEER system is part of the National Occupation Classification 2021 system. For more information, see this helpful site from the Government of Canada.

[2] See the 2021 Census summary reports for more detail.