Two of the most common myths around tourism employment are that it is (a) mainly for young people, and (b) low-paid and unreliable.

In other words, tourism doesn’t offer careers, it only offers short-term jobs for a transient and inexperienced workforce. These misconceptions have been around for a long time. They certainly don’t help when it comes to managing the sector’s reputation—and they are unfortunately hard to dislodge.

Part of this is a perceptual bias: when we travel during peak periods, we probably see a lot of young people in front-facing roles. Another part? Aggregate wage data doesn’t do a very good job of faithfully representing the complexity of pay across the tourism sector.

Young Workers in Tourism

It is undeniably true that the tourism sector employs more young people (aged 15 to 24) than tend to be employed across the economy as a whole. In the 2021 census, around 27% of tourism employees were in this age group, compared to only 12% across the entire Canadian labour force (spanning all industries and sectors). What’s more: this age group made up only 11.4% of the total Canadian population.

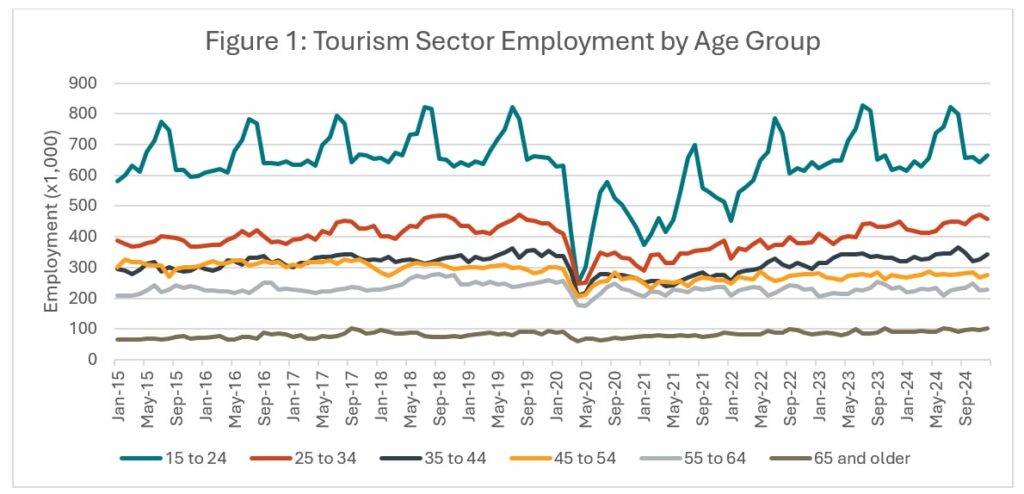

Figure 1 shows an age breakdown of tourism employment from January 2015 to December 2024.

In terms of raw numbers, young workers are the largest age cohort in the tourism workforce. There is an annual summer bump in tourism employment of around 100,000 young people, with an early increase in May when university and college students start their summer jobs, and a second in July when high school students enter the workforce.

The next-youngest age group (25 to 34) showed some cyclical seasonal growth before the pandemic, but that pattern has all but disappeared since the pandemic.

In spite of the magnitude of young workers in tourism, it is important to remember that the majority of workers are older than this (see Figure 2). While youth are certainly over-represented in the tourism workforce versus those of other sectors, they do not make up the bulk of our employees.

Young workers tend to end up in frontline positions, partly because of the shiftwork flexibility associated with these jobs, but also because they generally lack the skills and experience to start in a more senior position. This also means they will skew towards the lower end of the pay scale.

Our perception and sentiment research has found that around 50% of Canadians have worked in tourism at some point in their lives, but generally quite a long time ago; so if the average Canadian’s perception of tourism is based on their time as a young worker, they will likely be carrying certain assumptions that are not necessarily warranted.

One theme that emerged in both survey work and interviews with tourism employers is a widespread perception that “young people don’t want to work”. They cite instances of ghosting job interviews, of not showing up for shifts, of quitting with no notice—sometimes without telling their employer that they’re leaving. While these are no doubt frustrating incidents, it’s not entirely fair to paint an entire generation of workers with the same brush. Youth do want to work, but they may have different expectations than their bosses. This is a generation shift, exacerbated by the toll of growing up in economically, geopolitically, and environmentally fraught times. These pressures are not unique to youth, but they likely manifest differently because of their age and their life experiences.

Additionally, we’re currently working with a COVID-19 cohort: young people who were socially isolated from their peers during a critical developmental period of adolescence. They may be entering the workforce lacking some of the basic skills that employers are assuming they have, particularly around interpersonal skills, handling stress, and expectations of punctuality or showing up. Their schooling years were marked by a culture of extreme accommodation, and they will not have had volunteer or other opportunities to learn these behavioural expectations outside of school. They may also be entering the workforce for the first time at a slightly later age than we would have seen before the pandemic, which can also exaggerate the perception of some of these skills gaps: a 25-year-old today may be in the same position as a 17-year-old five years ago. This cohort will work its way through the system in time, but it’s likely that this will continue to be a factor in entry-level positions for another year or so at least.

The high rate of turnover among young tourism workers is another point that is often bemoaned, and one that tends to come up in discussions of labour issues. Why aren’t our retention rates higher? What can we do to hang on to these workers for longer? The fact is that tourism offers excellent entry-level jobs that introduce people to the labour market, attach them to employment that fits their needs at that moment, and develop highly employable and transferrable skills. Many doctors, lawyers, engineers, social workers, and teachers (to name but a few) worked their way through their studies in part-time and seasonal work in tourism, and for them, tourism jobs were never more than a stop along the way to a different career. However, the skills they learned in tourism will stay with them throughout their professional lives.

This is not to suggest that our sector can’t do a better job of retaining young workers as they transition from students to full-time workers. We should absolutely be working hard to better attract and retain the best and the brightest, and to nurture the future leaders of our sector from the start. Of course, this is easier said than done; employers have been trying hard for years to grow their workforces, in the face of increasing pressure from other sectors and shifting demographics.

So how can we shift the narrative—or at least the benchmark comparisons—against which tourism is judged?

Earnings Comparison Data

Comparing wages—or earnings—between different sectors is not as straightforward as it may at first seem, particularly when the sectors are structurally different from each other.

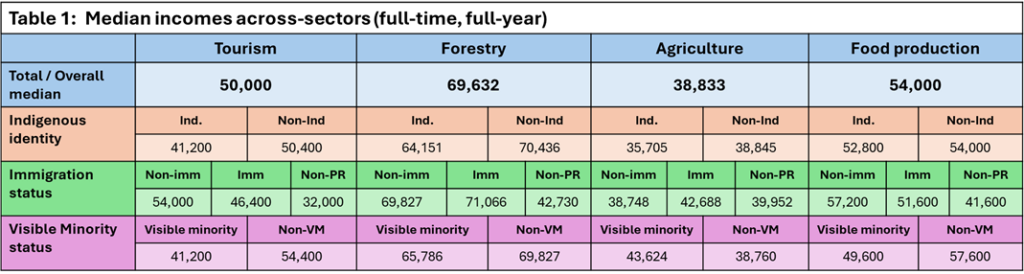

Table 1 provides a comparison along various demographic categories between tourism and three other sectors, taken from the 2021 census: forestry, agriculture, and food production. The choice of these three sectors was deliberate:

- Each sector has some degree of representation across most of the country (unlike, for example, vehicle manufacturing or oil and gas, which have a more restricted distribution).

- Each sector provides a low-barrier entry to employment. That is to say, each offers entry-level positions that don’t necessarily require any formal education or training to get a foothold in employment, but each offers the possibility of further advancement with a combination of training and experience.

- Each sector encompasses a range of different industry groups as defined in the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS 2022 v1.0) and covers a range of different occupations that will have different earnings profiles.

The data compares only full-time, full-year work in each sector. Each may be seasonal in its own way in different parts of the country, but the duration and type of seasonal work (and therefore the related earnings) between sectors does not align particularly well. Additionally, the income data available for this perspective does not distinguish between people working part-time and people working part of the year, and therefore conflates (for example) university students working 15 hours a week for eight months of the year with forestry labourers working 55 hours a week for seven months. Limiting the data to ‘regular workers’ by a traditional definition of full employment throughout the year allows us to have a reasonably reliable baseline for comparing between sectors.

This data presents median incomes rather than average incomes. Both statistics are measures of central tendency, but they have slightly different characteristics.

- The average (or arithmetic mean, to be more precise) is calculated by adding up all of the values (let’s say there are n numbers that you’re adding up) and dividing by the number of values (n). This is probably the most common measure of central tendency that we encounter in our daily lives, but it can be distorted by a small number of extreme values.

- The median is the number exactly in the middle of a set of values, when those values are arranged in increasing (or decreasing) order. The median is less sensitive to extreme values, and tends to skew towards the greater concentration of workers (either higher- or lower-earning).

In sectors such as these four, where are there are a greater number of workers on the lower end of the income scale than on the upper end, this means that the median will be lower than the average, making it a slightly more representative estimate of earnings.

Given these restrictions, it is interesting to see how tourism stacks up against these other sectors. Tourism income is comparable to that seen in food production and higher than in agriculture, but lower than in forestry. The broad patterns across the different demographic categories are generally very similar: non-Indigenous people tend to earn more than Indigenous people; non-immigrants tend to earn more than immigrants or non-permanent residents; and non-visible minorities tend to earn more than visible minorities. One exception to this is agriculture, where non-immigrants earn less than either immigrants or non-permanent residents, and where visible minorities earn more than non-visible minorities. But on the whole, the earnings structure for these four sectors is generally quite similar even if the actual incomes are different.

It’s not clear to what extent tips and other gratuities are included in these income estimates. The census aims to include these, but the data collection relies on self-reporting—and where tips are not attached to a payslip, they may be under-reported. If that is the case, then the income for tourism is likely somewhat higher, given the large percentage of the tourism workforce who work in food and beverage services, where tipping is common practice.

Of course, these income estimates do not include other perks or benefits: registered pension plan contributions, EI premiums, and medical/dental/accident insurance are excluded, which can effectively increase the value of an employee’s remuneration, depending on the conditions of employment. Those who are self-employed or who work for very small firms may have less access to such benefits. Similarly, non-monetary rewards such as personal use of facilities, free meals, and discounted access to other services can also add value—and many tourism businesses have a lot to offer to sweeten their deal.

Gender Earnings Gap

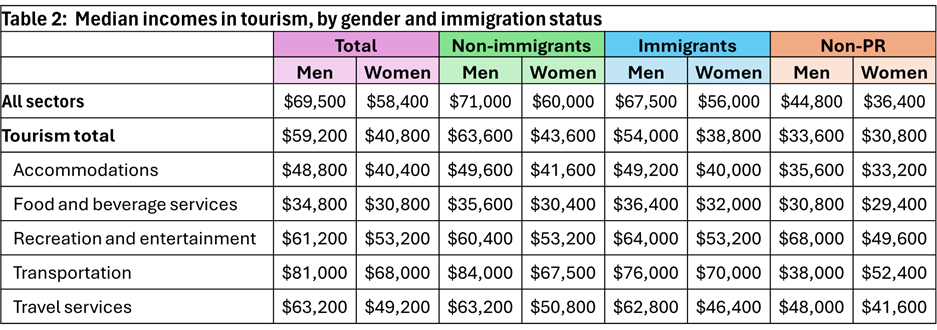

The previous table did not include any gender data, a limitation of the data sets that Tourism HR Canada has available as they pertain to sectors other than tourism. However, we are able to provide a snapshot of gender differences in pay across the tourism sector, including immigration status as a social variable (see Table 2). As with the Table 1, this only considers those working full-time, full-year.

In the aggregate, women in tourism have a median income of around 69% that of men, considerably lower than their relative income across all sectors (84%). What is interesting is that the gender earnings gap in tourism employment is generally larger for non-immigrants than it is for immigrants and non-permanent residents. At the sector level, non-immigrant women earn 69% what comparable men earn, while immigrant women earn 72% and non-permanent resident women earn 92%. Without much more detailed data, is it not possible to fully unpack these differences, but it may have to do with the types of jobs that different people take up: in particular, many non-permanent residents will likely be in relatively entry-level positions (as evidenced by the lower overall incomes), where earnings gaps will likely be smaller across the board.

It is important to note that we are discussing an earnings (or income) gap, not necessarily a wage gap. To really establish that there is a wage gap, it is necessary to compare specific jobs in similar companies, and with comparable tenures in those roles—and this level of detail is not available in the census data, unfortunately.

While there are no doubt numerous examples of a gender pay gap in the tourism sector, there are other structural challenges that women face that directly and indirectly impact their earnings, and without taking these into consideration, estimating the actual wage gap is impossible. Time spent away from the workforce, for instance for childcare or other caring responsibilities (both of which still fall disproportionately on women), can slow down career progression relative to those who do not take time away, and end up keeping women out of top-paying senior management positions. Women who spend time away from work may also change jobs when they re-enter the workforce, meaning they may be starting again at the lower end of the pay scale for a given position. They may also come back in a part-time or temporary position, which will also slow promotion trajectories but would not directly have an impact on this data set, as it excludes part-time and seasonal workers.

Countries that tend to have a smaller wage gap are also countries that have robust and supportive social programs to support women’s attachment to the workplace, and to balance caring responsibilities more evenly across family members. Tourism certainly must do better than it is currently doing, but there must also be improvements in Canada’s social system to enable women to thrive in tourism careers. We need more granular data to identify where the specific challenges are, and to implement the right changes to make the tourism workplace more welcoming and accommodating.

The Value Proposition

Tourism jobs will never compete with certain other sectors on a strictly wage basis. Oil and gas, for instance, will always be able to out-pay what tourism operators can, because the profit margins are so much smaller in our sector. On the other hand, working in tourism is a completely different lifestyle from working in oil and gas, and those who don’t want to live in an oil patch may have priorities other than money.

In fact, tourism has a lot to offer that other sectors don’t, and it’s down to businesses and operators to market their value proposition to their (future) employees just as proudly as they market their products and services to their customers.

- Lifestyle. While some people criticize tourism for its ‘unsocial hours’, the fact is that tourism jobs offer a degree of flexibility that accommodates people’s unique needs. For those who want to work nine to five, those jobs absolutely exist—plus there are diverse work opportunities for those looking for evenings and weekends, for those balancing two jobs, for those looking to work around their family commitments. Operators can be more flexible in how they schedule shifts to attract and retain a wider range of worker needs.

- Work environment. Some tourism businesses are surrounded by unparalleled landscapes and wildlife; others are in the heart of thriving and exciting cities. Tourism businesses operate where people want to visit, and the attraction of these places can also appeal to people looking to live someplace they love. Businesses can entice jobseekers with free or discounted access to local attractions or services, or can offer to support around housing or transport, both of which are barriers facing many looking for work, particularly in rural or remote areas.

- Work conditions. No job is entirely without risk, but many jobs in tourism are inherently safer than some of the higher-paying jobs in heavy industry, resource extraction, or agriculture. Tourism also caters to a range of work preferences: there are jobs working indoors or outdoors, working with people or alone, drawing on technical skills or social skills, at a fast-paced clip or in a more relaxed setting. The variety of jobs available tends to be masked by first impressions of the frontline work that many people pick up in their youth. We need to better highlight the range of opportunities available in tourism to suit everybody and anybody.

- Job growth. Some tourism businesses have a more clear-cut promotions track—large hotels and restaurants, for instance, tend to be vast and complex organizations, and may have a centralized office that oversees multiple properties or locations. But the absence of hierarchies in smaller enterprises may make it seem that there is no point in staying long term. If there is no ‘up’ to aspire to, why invest the time? Rewarding job longevity through financial means (e.g., pay increases) and/or non-monetary perks (e.g., more vacation days) can signal to employees that they are valued members of a team, and increasing responsibilities to create new roles can skirt the issue of vertical promotion in non-hierarchical organizations.

- Sustainability. Tourism is poised to become an integral part of the regenerative economy, with many businesses already investing in ecological and social solutions to protect the environment and the communities where they are based. Marketing the social responsibility and ecological commitments of tourism businesses can be a useful tool in attracting those looking for meaningful work: for someone looking for a job that aligns with their personal values and offers the opportunity to enact positive change in a turbulent world, tourism offers more options than they may at first realize. Businesses need to do a better job of framing their enterprise and their openings in these terms.

Every tourism business will have its own value proposition, depending on what kind of business it is, where it’s located, whom it serves, and the ethos and philosophy of its operators. But there are common threads that are woven through the tourism sector that are a strong foundation from which to re-tell the story of working in tourism. The narrative of low-paid, dead-end jobs for youth needs to change, and being more strategic about what tourism has to offer is a good starting point.

Changing How You Approach Attraction and Retention: Worker Archetypes

As well as rethinking the value proposition that businesses present to job seekers, operators can also think strategically about whom—exactly—they are trying to attract in the first place, and what they can offer to entice them in. This may be a different approach for some managers or operators, who have not needed to adopt such a targeted or strategic recruitment approach in the past. The COVID-19 pandemic substantially changed both business practice and labour force expectations, and against this new backdrop, a new set of tools is needed to meet the labour challenges in the tourism sector.

Over the past two years, Tourism HR Canada has been developing worker archetypes. These personas grew out of a careful qualitative analysis of survey findings, interviews, and focus groups, and were initially put together as a tool to help businesses tailor their compensation packages to suit different pools of jobseekers. The five archetypes we have developed thus far are given below (1-5), along with a sixth that we are beginning to explore in more depth (6).

- Adventurers. These jobseekers and workers tend to be young (although not always—there are some career adventurers out there), and are looking for work that supports a lifestyle of seeking adventure. They include students, those on a working holiday visa, and people chasing a passion (e.g., following the ski season between the northern and southern hemispheres). They may be drawn to seasonal work, particularly in areas with easy access to the things that excite them. Some may have technical skills or certificates related to their interest and are looking for work in that field, and others may be interested in any work that gives them time to play. They’re likely looking for short-term employment, but they may be in the market for regular seasonal work, and they’re connected to networks of other adventurers. These workers are more likely to be interested in short-term perks (e.g., staff accommodation, ski passes, free meals) than more traditional benefits (e.g., RRSP contributions, dental plan).

- First jobbers. These workers and jobseekers also skew young, but they are looking for more stability than adventurers are. They may be recent graduates from college or university, and bring limited life and work experience with them, but they are looking for work that they find meaningful or interesting. They likely are still trying to figure out who they are and what they want from their grown-up life. They will be drawn to a mix of lifestyle perks and financial incentives, but a bit of flexibility will go a long way—for example, offering student loan repayment assistance instead of a retirement plan. They may be open to career development, but are probably not aware of the possibilities that tourism offers. They are looking for a job, but could be retained longer term if they feel they are being treated well and a clear plan for progression is presented to them.

- New Canadians. This is quite a disparate group of workers and jobseekers, covering a wide range of ages, backgrounds, cultures, and languages. They will have overlapping experiences of adjusting to living and working in Canada, and are looking for recognition of their prior experience and qualifications. They often have a less jaded view of working in tourism than many other Canadians, and may be amenable to long-term work if they feel they are being treated well and compensated fairly. They will thrive in a supportive and welcoming environment that celebrates diversity, and where they feel like part of the team. Having easy and early access to benefits that include their family members may be particularly important, and those recently arrived in Canada may appreciate English or French language support for their entire families, as well.

- Adulting or mature workers. This group represents those at a point in their lives when their personal and professional priorities begin to change, and young workers begin to orient to more traditional markers of adulthood. They are looking for increased financial stability and a grown-up career plan, preferably doing something they find challenging and meaningful and that aligns with their values. They will be attracted to a competitive compensation package tied to a flexible schedule that can accommodate personal obligations. A structured program of professional development and training towards recognized credentials may be particularly attractive to these workers and jobseekers, along with mentorship from someone who can help them reach their potential.

- Second acts. This group of jobseekers are those are coming to tourism after a career in another sector: they may be changing careers, taking on a second job, looking for retirement income, or simply making big changes in their life. What they lack in tourism experience they make up for in transferable skills and other work experience, so recognizing and rewarding the skills they bring with them is key. They will prioritize a workplace that aligns with their values, and are looking for a relationship of mutual trust and autonomy. Because this group is potentially as diverse as the New Canadians, a highly customizable compensation package will be useful in attracting and retaining them.

- Future entrepreneurs. This is the newest—and least-developed—archetype so far, and it is currently based on only a few observations, so lacks detail. These are people with an entrepreneurial drive, but who lack the experience, training, or confidence to open their own company just yet. They may or may not be drawn to tourism specifically, but a job offer framed as an opportunity to learn about all aspects of running a business may appeal to them. A two-year plan that progressively builds their leadership and managerial skills through exposure to different aspects of the business will help them fully engage with a company. They may not end up as long-term employees, but they will be hard-working, engaged, and motivated while you have them.

Since we first developed these archetypes, we have been thinking about other ways that they may be useful in our sector. They remain a work in progress as we collect more insights from employers and employees, but they remain a useful framework for developing flexible compensation packages. We invite interested readers to take a look at our Compensation Culture series of infographics and worksheets, and to explore the set of tools available for working with smaller and more nimble teams.

Money Matters, but It’s Not the Whole Story

With a smaller pool of workers and tightening economic times, the tourism sector needs to be creative in our value proposition, both for attracting new workers and retaining the ones we already have. At the sector level, our wages are broadly comparable to some of our closer competitors in terms of barriers to entry and geographic distribution, but we also offer a host of non-monetary benefits and advantages that we could better leverage to highlight working in tourism. Having an attractive and competitive compensation package doesn’t have to break the bank if operators are willing to be flexible and get creative in how they market themselves. It may mean changing what HR looks like in practice, but there are tools available to support that transition.

We tend to focus on younger workers when we’re looking for talent, and there are good reasons why this sector provides employment for so many youth—but we also need to think further afield. Engaging more deliberately with older workers—particularly Second Acts—will be increasingly important as the demographics in the Canadian population shift over the coming years. Immigration policies are undergoing close scrutiny and reconfiguration at the moment, but there are many international people already in Canada that we are not tapping into: international students often have no difficulty finding work outside of their school hours, but there are many refugees, asylum seekers, and displaced persons who want to work. Connecting with settlement support agencies can help tap into pools of New Canadians without having to tackle the immigration system directly. And opening up opportunities for other underemployed Canadians—those with disabilities, for instance—is another fruitful avenue to explore. Tourism HR Canada’s Belong project is developing tools and networks to support businesses in making their workplaces more open and accessible for all.

Tourism HR Canada continues to explore sources for new data relating to wages, because we understand how important it is for businesses, advocacy bodies, government, and the general public to have access to the best information on the labour market in tourism across Canada.

Keep an eye on our tourism employment tracker dashboard and sign up for our Tourism HR Insider newsletter to stay up to date on the state of the sector in Canada.

This is the second in a series of articles looking at key topics that came out of our recent Losing Ground: The Definitive Workforce Update webinar. Read the first article, International Talent in Canadian Tourism, and be sure to subscribe to Tourism HR Insider for the next analysis.